Week to week changes in judo periodization

CONTENTS

- Introduction

- What is week to week variability

- How to calculate week to week variability

- Examples

- Application

- JudoTraining Load V1.0

- Free excel sheet

- Conclusions

- References

INTRODUCTION

Progressively increasing training stress is necessary to improve performance (8) but how much is enough and how much is too much?

In this article I will try to explain more about week to week changes and how important is that coaches control the variability of weekly training load, in order to create positive training adaptations. I will also provide information about how to calculate the weekly change and its practical applications in judo periodization.

WHAT IS WEEK TO WEEK CHANGES?

In order to elicit adaptations and ultimately improve in our training, making sure we are progressing week to week is key. Variations of load between weeks, and their relationships with the load distribution can be extremely important in determining the effects of training on a athlete’s performance and, most of all, to understand the impact of training strategies on the adaptations of athletes. This knowledge could help coaches to know the training loads imposed on each microcycle and to design appropriate training tasks in order to ensure the specific judo demands (1)

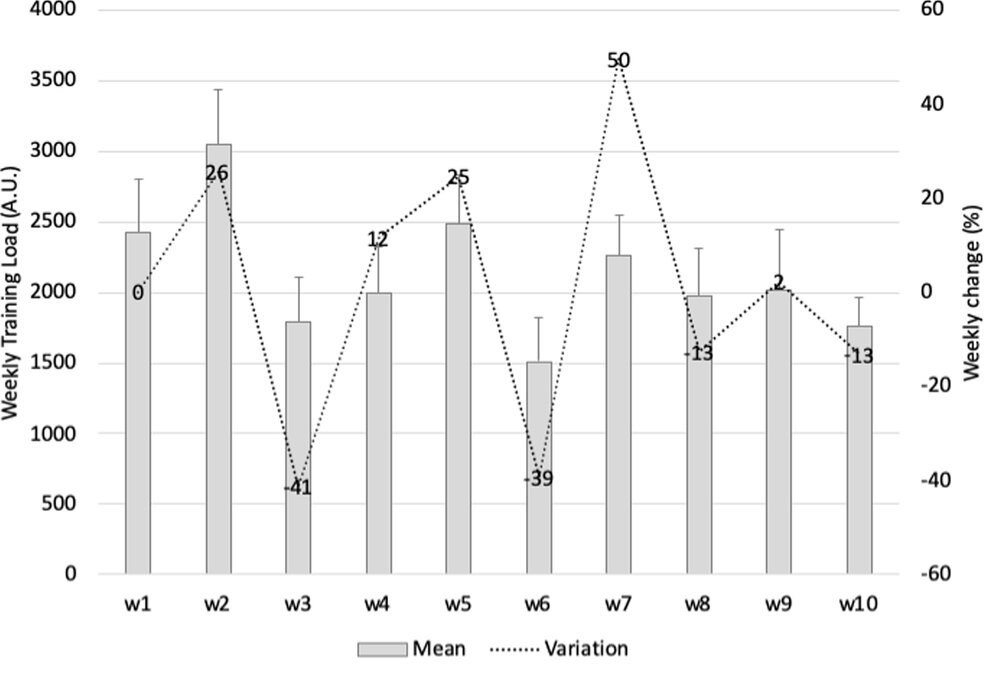

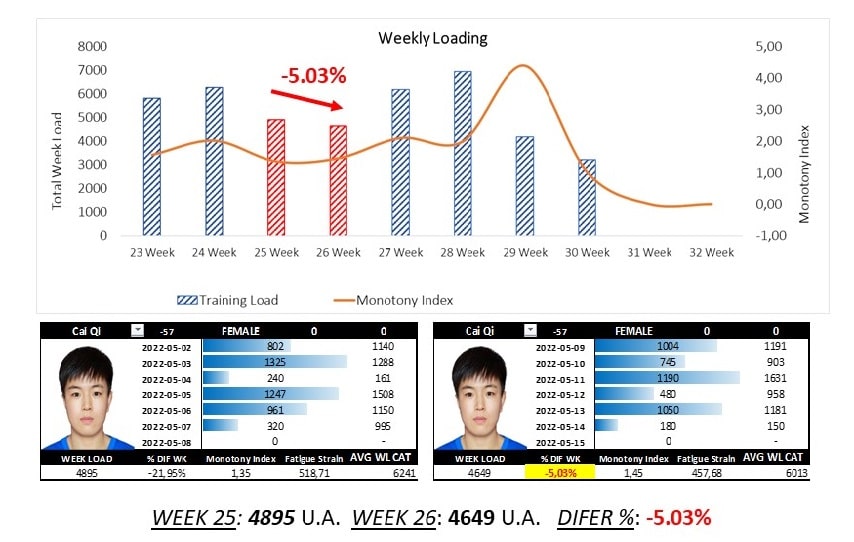

In the research carried out by Clemente et al. (1) we can see one example about how is the weekly variation (%) during 10 weeks in professional soccer players (Fig.1).

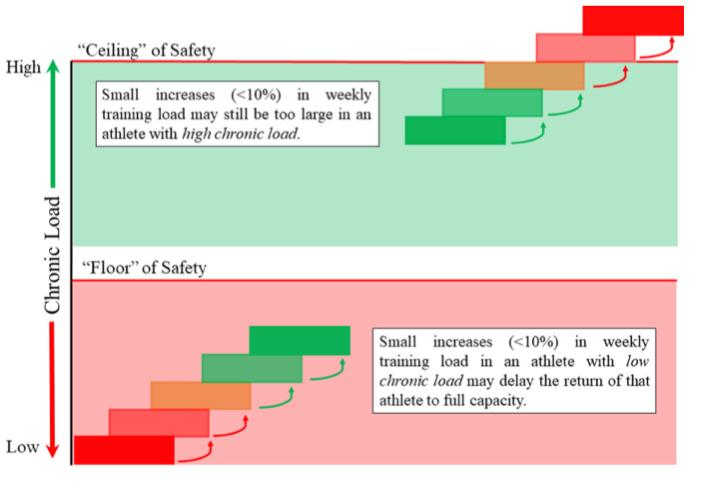

Gabbet (5) suggested that to minimize the risk of injury, all athletes should restrict their weekly training load increases to less than 10%. However, with most scientific findings, context matters! Although the general consensus is that rapid changes in training load increases the risk of injury, changes in training load should also be interpreted in relation to the athletes’ chronic load. Athletes with low chronic load have greater scope for increases in training load, while athletes with high chronic load have a much smaller scope to increase their training load. It is much easier to increase weekly training load when the chronic load is near the ‘floor’ than when it is near the ‘ceiling’.

HOW TO CALCULATE WEEK TO WEEK VARIABILITY

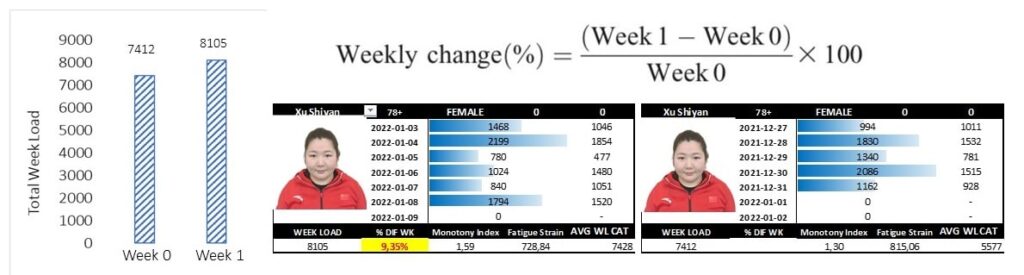

Weekly change is calculated as the percentage change from the cumulative sum of the current week (Week1) relative to the cumulative sum of the previous week (Week0) (9)

Weekly change % = ((Week 1 – Week 0)/ Week 0)*100

EXAMPLES

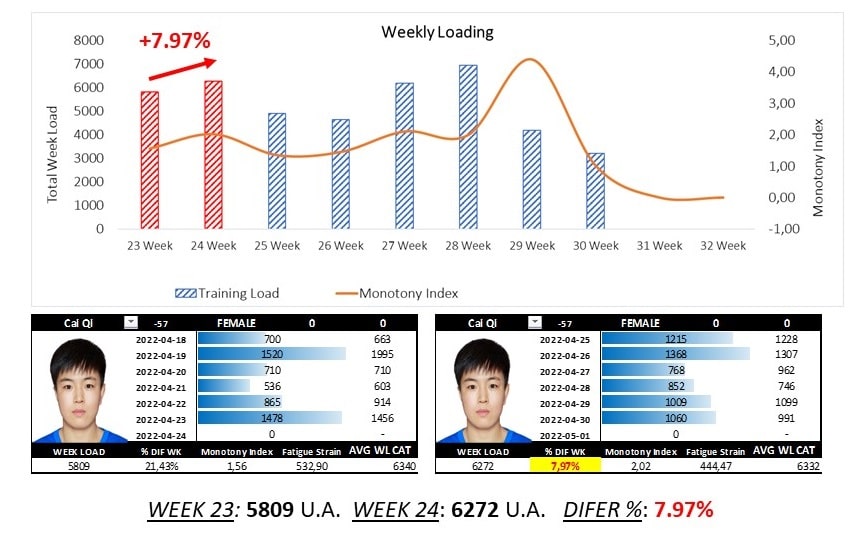

In Fig.4 and 5 we can see a real examples about how to calculate the variation of weekly training load. In Fig. 4. we can see that on week 24 the training load increased from 5809 to 6272 ual, 7.97% more and in Fig. 5 the training load decreased from 4895 to 4649 ual, 5.03% less.

APPLICATION

- Control the weekly variation will help us to monitor if load planned in the different microcycles is the same than load perceived by athletes. In this example we can see the weekly variation between Week 3 and Week 4. The Week 3 was a developmental microcycle and the Week 4 was a shock microcycle (Fig. 6).

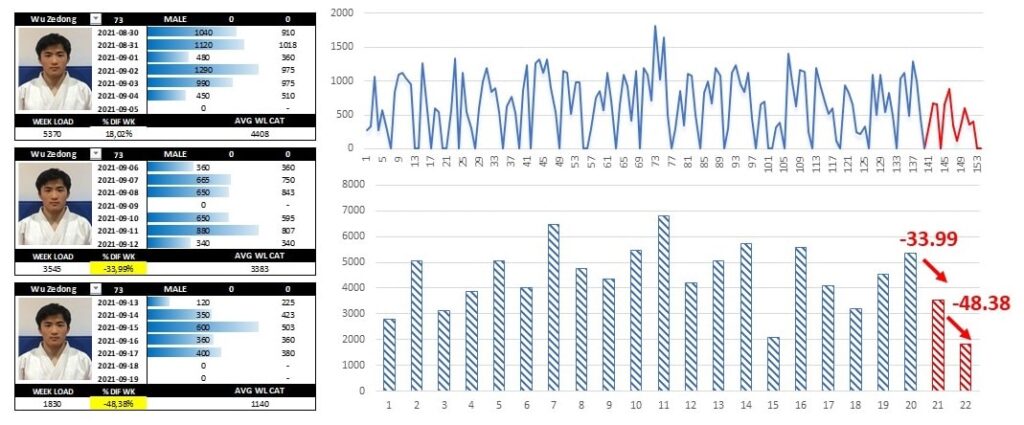

- The taper or “the short-term reduction in training load before competition” (9) is a normal practice in sport performance in an attempt to reduce the physiological and psychological stress of daily training and optimize sports performance. Monitoring daily/weekly training load is crucial to check if the reduction of training load is real, In the next example we can see the taper phase on the last two weeks of the preriodization before an important competition. The judo athlete decreased his training load 33% one week before the competition and 48%, on the week of the competition.

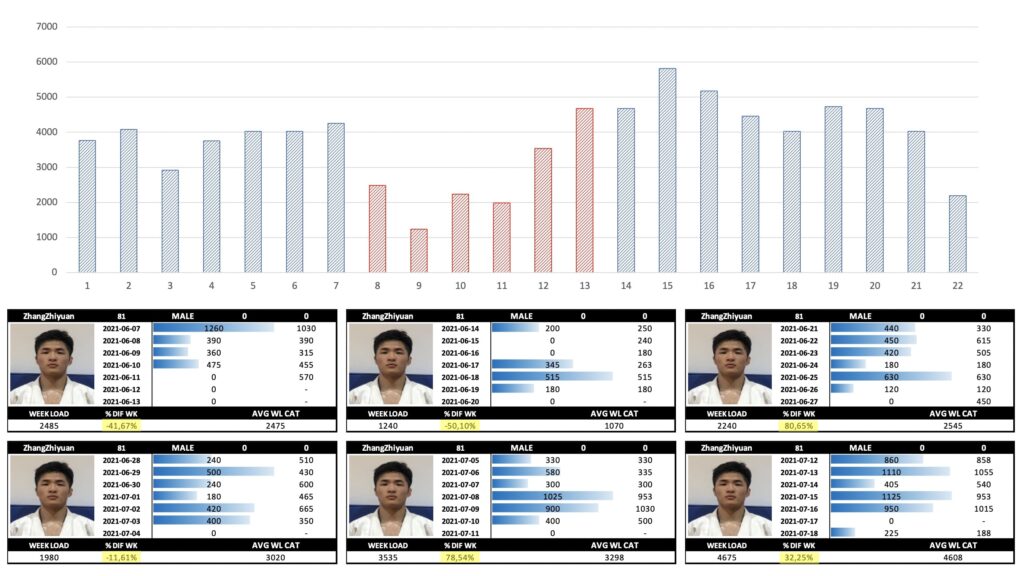

- With weekly variation we can check how is the progression on athlete´s preparation so this variation will give us very valuable information when it comes to adjusting future sessions and microcycles. In this example, the athlete was seriously injured on Week 8, reducing the training load. After several weeks focused on recovering from the injury, we began to increase the training load in a progressive manner. Monitoring this weekly variation will allow us to control the training load in an individualized way, minimizing risks and trying to enable the athlete to return to training with the rest of the team normally.

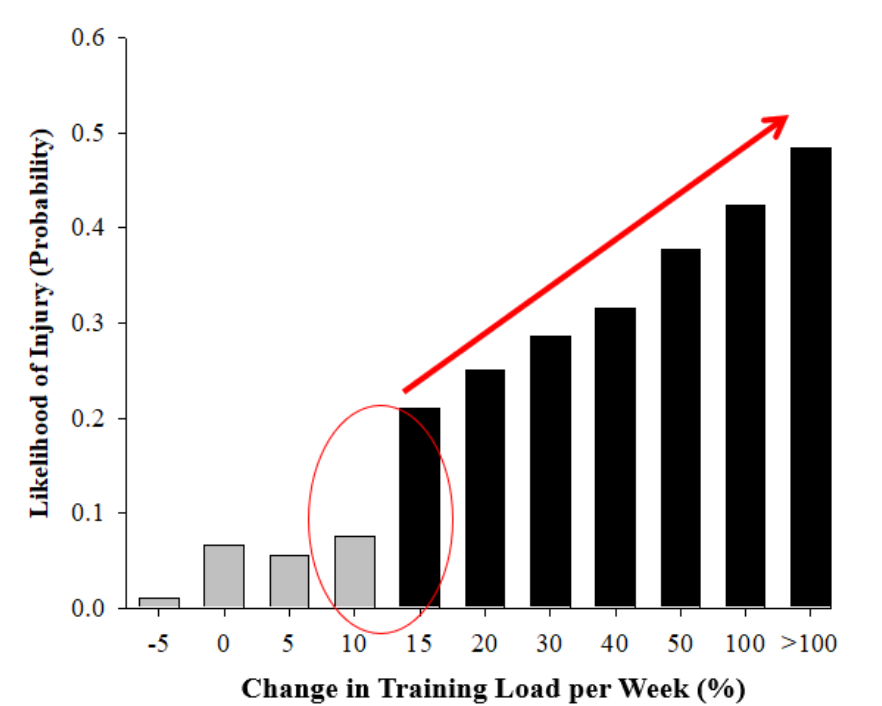

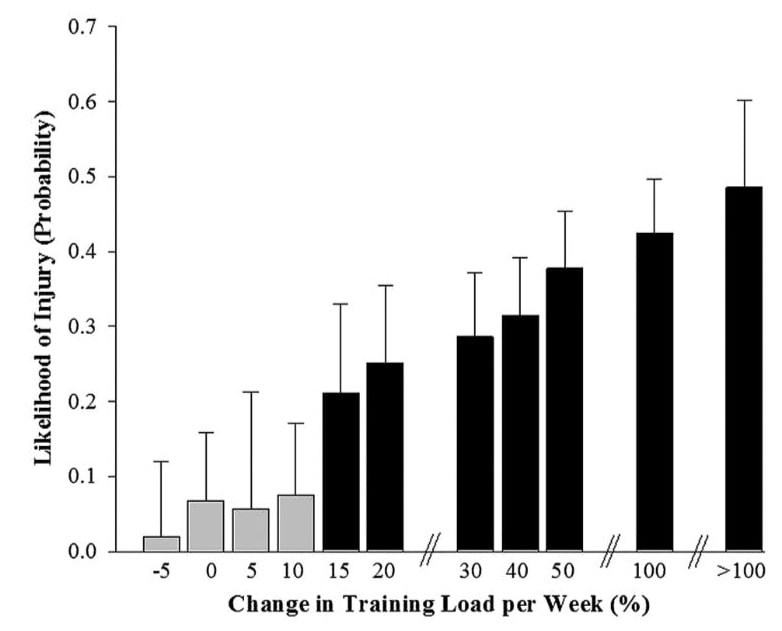

- Progressively increasing training stress is necessary to improve performance (9). However, researchers and clinicians are concerned that a sudden change in training stress (ie, ‘‘too much, too soon, too fast’’) increases the risk of sustaining an injury (2,11). Week-to-week changes in workload of more than 10–15% were related to increased injury risk (4). Gabbet el al. (4) have modelled the relationship between changes in weekly training load (reported as a percentage of the previous weeks’ training load) and the likelihood of injury, When training load was fairly constant (ranging from 5% less to 10% more than the previous week) players had <10% risk of injury (Fig.10). However, when training load was increased by ≥15% above the previous week’s load, injury risk escalated to between 21% and 49%. To minimise the risk of injury, practitioners should limit weekly training load increases to <10%. According to these findins and other is important to control the weekly training load and compare with previous week, in order to check the increase/decrease and to adjust the loads for the following microcycles.

- Although the general consensus is that large weekly changes in training load increase the risk of injury in both individual and team sport athletes, these changes in training load should be interpreted in relation to the chronic load of the individual athlete. For example, small weekly increases in training load (≤10%) in an athlete with low chronic training load will considerably delay the return of that athlete to full capacity, whereas an athlete with high chronic training load will likely tolerate much smaller increases in training load from week to week (figure11). In this respect, limiting training load increases to 10% per week is, at best, a ‘Guideline’ rather than a ‘code’ (6)

JUDOTRAINING LOAD V1.0

Now you can calculate week to week changes and other interesting measurements with our Excel Sheet JudoTraining Load V1.0 and take your’s team performance to the next level.

If you would like to know more information about this new tool for judo coaches, you can check it out HERE and download the brochure with all information.

FREE EXCEL SHEET

Download here this free Excel sheet and you will be able to calculate easily the weekly change of your microcycles.

CONCLUSIONS

- Understanding how to measure weekly variation allows us to easily manage our training progression according to what require, whether that is a light week for recovery or a harder week for progression.

- Progressively increasing training stress is necessary to improve performance but we must understand that a sudden change in training stress (ie, ‘‘too much, too soon, too fast’’) increases the risk of sustaining an injury (2,11)

- Periods of deloading, where there is a lack of activity, followed by a return to training, is also high risk of injury. These changes in activity are often considered “training load errors” (3).

- Don’t increase/decrease training loads greater than 10% from week to week.

- What can be measured can be managed. Use week variability tracking to ensure a correct load progression and minimize the risk of injuries.

REFERENCES

1. Clemente FM, Clark C, Castillo D, Sarmento H, Nikolaidis PT, Rosemann T, et al. (2019) Variations of training load, monotony, and strain and dose-response relationships with maximal aerobic speed, maximal oxygen uptake, and isokinetic strength in professional soccer players. PLoS ONE 14(12)

2. Damsted C, Glad S, Nielsen RO, Srensen H, Malisoux L. Is there evidence for an association between changes in training load and running-related injuries? A systematic review. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2018;13(6):931–942.

3. Drew, M. K., & Purdam, C. (2016). Time to bin the term ‘overuse’injury: is ‘training load error’a more accurate term?. Br J Sports Med, 50(22), 1423-1424.

4. Gabbett, Tim. (2016). The training-injury prevention paradox: Should athletes be training smarter and harder?. British journal of sports medicine. 50. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095788.

5. Gabbett, T. When Progressing Training, Not All Load is Created Equally. https://southcoastseminars.com/blog/2018/10/14/when-progressing-training-not-all-load-is-created-equally

6. Gabbett TJ. Debunking the myths about training load, injury and performance: empirical evidence, hot topics and recommendations for practitioners. Br J Sports Med. 2020 Jan;54(1):58-66.

7. Garcia MC, Pexa BS, Ford KR, Rauh MJ, Bazett-Jones DM. Quantification Method and Training Load Changes in High School Cross-Country Runners Across a Competitive Season. J Athl Train. 2022 Jul 1;57(7):672-677.

8. Gibala, M. J., J. D. MacDougall., and D. G. Sale. The effects of tapering on strength performance in trained athletes. Int. J. Sports. Med. 15:492–497, 1994.

9. Meeusen R, De Pauw K. Overtraining syndrome. In: Hausswirth C, Mujika I. Recovery for Performance in Sport. Human Kinetics; 2013:9–20.

10. Nielsen RØ, Parner ET, Nohr EA, Sørensen H, Lind M, Rasmussen S. Excessive progression in weekly running distance and risk of running-related injuries: an association which varies according to type of injury. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014 Oct;44(10):739-47

11. Soligard T, Schwellnus M, Alonso JM, et al. How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(17):1030–1041.

Check this article out about “Using Training Monotony to design better judo programs”

Great beat ! I would like to apprentice while you amend your web site, how could i subscribe for a blog site? The account helped me a acceptable deal. I had been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast provided bright clear concept

I want to thank you for your assistance and this post. It’s been great.

Pingback: buy backlinks usa

Pingback: Davidoff Cigars

Pingback: สร้างกำไรจาก สล็อตเครดิตฟรี

Loose leaf wraps have grown in popularity among tobacco lovers who want a genuine, personalized smoking experience. Unlike pre-rolled cigarettes, looseleaf wraps enable users the ability to roll their own masterpieces by hand, adding a unique touch to every smoke.

loose leaf wraps

loose leaf

looseleaf

loose leafs

looseleaf wraps

loose leafs wraps

loose leaf blunt

loose leaf blunt wraps

loose leaf blunts

loose leaf woods

looseleafs

where to buy loose leaf wraps

loose leaf wraps near me

loose leaf rolling paper

loose leaf wraps wholesale

loose leaf backwoods

loose leaf russian cream

leaf wraps

loose leaf flavors

loose leaf backwood

strawberry loose leaf

loose leafs near me

loose leaf wrap

loose leaf ice cold

loose leaf honey bourbon

loose leaf reserve

loose leaf banana dream

loose leaf strawberry dream

loose leaf minis

loose leaf tobacco

loose leaf mini

loose leaf cigars

loose leaf box

ice cold loose leaf

loose leaf near me

loose leaf wraps for sale

loose leaf iced cold

loose leaf strawberry

loose leaf cigar

loose leaf blunt wraps near me

looseleaf wraps near me

looseleaf wholesale

loose leaf price

russian cream loose leaf

desto dubb loose leaf

looseleaf minis

smokelooseleaf

loose leaves

loose leaf natural dark leaf

lose leafs

lose leaf

watermelon loose leaf

red rum loose leaf

leaf wrap

rolling leaf

loose leaf banana

honey bourbon loose leaf

box of loose leafs

looseleaf strawberry dream

banana dream loose leaf

banana loose leaf

looseleaf blunt wraps

looseleafs wraps

loose leaf desto dubb

loose leaf tobacco wrap

loose leaf tobacco near me

loose leaf ice

loose leaf woods near me

strawberry dream loose leaf

loose leaf packs

reserve loose leaf

loose leaf tobacco wraps

loose leaf wood

loose leaf iced cold wraps

watermelon dream loose leaf

looseleaf flavors

loose leaf watermelon

rolling leafs

loose leaf pack

loose leaf paper wraps

loose leaf watermelon dream

loose leafs flavors

loose leaf wraps box

loose leaf wraps flavors

looseleaf mini

loose leaf cigars near me

loose leaves woods

strawberry loose leaf wraps

loose leaf strawberry dream near me

loose leaf wholesale tobacco

backwoods loose leaf

desto dubb woods

looseleaf ice cold

ice loose leaf

desto dubb loose leaf near me

trippie redd loose leaf wraps

loose leaf reserve black edition

new loose leaf

loose leaf wraps ice cold

loose wraps

loose leafs wraps near me

loose leaf backwoods near me

ice cold looseleaf

Your articles are extremely helpful to me. May I ask for more information?

Pingback: วิเคราะห์บอล

You could certainly see your enthusiasm in the work you write. The world hopes for even more passionate writers like you who are not afraid to say how they believe. Always follow your heart.

Hi there mates, nice post and nice urging commented here,

I am genuinely enjoying by these.

my blog post; vpn special code

hello there and thank you for your information – I’ve definitely picked up something new from right here.

I did however expertise several technical issues using this site,

since I experienced to reload the web site a lot of times previous to I could get it to load correctly.

I had been wondering if your web host is OK? Not that I’m complaining, but sluggish loading instances

times will sometimes affect your placement in google

and can damage your quality score if advertising and marketing with Adwords.

Well I’m adding this RSS to my e-mail and could look out for much

more of your respective exciting content. Make sure you update this again very soon.

Also visit my homepage – vpn special

I loved as much as you’ll receive carried out right here.

The sketch is tasteful, your authored material stylish.

nonetheless, you command get bought an edginess over that

you wish be delivering the following. unwell unquestionably come further formerly again as exactly

the same nearly a lot often inside case you shield this hike.

Feel free to surf to my page: vpn special coupon code 2024

Pingback: Bilskrot Partille

Pingback: แผ่นซับเสียง

I have to thank you for the efforts you have put in writing this site.

I really hope to check out the same high-grade

content from you later on as well. In fact, your creative writing abilities has inspired me to get

my very own site now 😉

You’ll then focus on web link variety, a vital

component for a durable SEO strategy.

Feel free to surf to my web site – Gsa ser link list

Pingback: counseling fairfax va

Hi there, this weekend is fastidious for me, because this moment i am

reading this great informative post here at my residence.

Hello, i believe that i saw you visited my web

site thus i got here to go back the choose?.I am attempting to

find issues to improve my web site!I guess its adequate to use some of

your concepts!!

Ahaa, its pleasant conversation regarding this paragraph here at this website, I have read all that, so

at this time me also commenting here.

I blog frequently and I really appreciate your information.

Your article has truly peaked my interest. I’m going to book mark your blog

and keep checking for new details about once per week.

I subscribed to your RSS feed as well.

I was wondering if you ever considered changing the page layout of your

site? Its very well written; I love what youve got to say.

But maybe you could a little more in the way of content so people could connect with it better.

Youve got an awful lot of text for only having 1 or two images.

Maybe you could space it out better?

Ahaa, its pleasant conversation concerning this post here at

this website, I have read all that, so at this time me also commenting here.

I will immediately snatch your rss as I can’t to find your e-mail subscription hyperlink or newsletter service.

Do you have any? Please let me realize in order

that I may just subscribe. Thanks.

I read this article fully about the difference of most recent and

previous technologies, it’s amazing article.

Howdy just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The words in your post seem to be

running off the screen in Firefox. I’m not sure if

this is a formatting issue or something to do with browser compatibility but I figured I’d post to let you know.

The layout look great though! Hope you get the issue fixed soon. Many thanks

What’s up to every single one, it’s actually a pleasant for me

to visit this site, it consists of useful Information.

Finding your website was a delight. It’s filled with insightful content and engaging commentary, which

isn’t easy to come by these days. value the effort you’ve

put into your writing.

Your writing style is impressive. You offer a novel viewpoint that

has sparked my interest. Can’t wait to reading what you post next.

I just had to leave a comment. Your articles speak with me on a profound level.

If you’re thinking about offering a newsletter, sign me up!

It would be a pleasure to have your insights sent right to my inbox.

Your article struck a chord with me. Rarely do you come across a blog that invites you to reflect.

I’m excited to read more of your thoughts and urge you to carry on with your passion.

Your article was a refreshing change. With an overwhelming amount of information online, it’s fantastic to find content that’s as enriching and entertaining as

yours. Looking forward to more

This syntax provides a variety of options for creating a

positive and encouraging blog comment that compliments the

author’s work and expresses a desire to continue engaging with their

content.

From time to time, I stumble upon a blog that truly stands out because of its thought-provoking articles.

Yours is without a doubt one of those rare gems.

The way you interlace your words is not just informative but also incredibly engaging.

I applaud the dedication you show towards your craft and eagerly look forward to your future posts.

Amidst the vastness of the digital world, it’s a pleasure to encounter a writer who invests genuine passion into

their work. Your posts not only offer valuable insights but also stimulate meaningful dialogue.

Count me in as a regular reader from this point forward.

Your blog has quickly risen to the top of my

list for me, and I find myself visit it frequently for new content.

Each post is like a masterclass in the subject matter, conveyed with clarity and wit.

Might you creating a subscription service or a periodic newsletter?

I would be thrilled to get more of your expertise straight to my inbox

The unique angle you bring to issues is both refreshing and rare, it’s

immensely appreciated in the modern online landscape.

Your ability to dissect complex concepts and offer them in an understandable way is a talent that should be celebrated.

I am excited for your future publications and

the dialogues they’ll foster.

Discovering a blog that acts as both a mental workout and a warm discussion. Your posts accomplish that, offering a perfect mix

of knowledge and personal connection. The audience you’re cultivating here is testament to

your influence and proficiency. I’m anxious to see where you’ll take us next and

I’ll be following along closely.

After investing countless hours diving into the depths of

the internet today, I feel compelled to express that your blog is like a lighthouse in a

sea of information. Not once have I stumbled upon such a trove of intriguing thoughts that resonate on a substantial level.

Your penchant for shedding light on complex subjects with elegance and acuity is

worthy of admiration. I’m patiently waiting for your subsequent piece,

knowing it will enrich my understanding even further.

In today’s age of information, where information overload is common,

your blog stands out as a pillar of originality. It’s a joy to find a corner of the web

that adheres to cultivating mindful learning. Your articulate posts stimulate a desire for learning that many of us crave.

I would be honored if there’s a way to subscribe for direct notifications, as I wouldn’t want

to miss any insightful post.

Your online presence is a testament to what engaged storytelling

is all about. Each article you create is filled with valuable takeaways

and rich narratives that keep me thinking long after I’ve read them.

Your perspective is an invaluable contribution to the often noisy online world.

If you have an exclusive membership, count me as a committed member

to join. Your writing is deserving of supporting.

I find myself visiting to your blog time and again, drawn by the quality of conversation you provoke.

It’s evident that your blog is not merely a platform for sharing concepts; it’s a gathering for

curious minds who desire substantive engagement. Your investment inOf course!

When I began exploring your blog, I realized it was something extraordinary.

Your skill to plunge into complex topics and clarify them for

your readers is truly impressive. Each post you release is a repository

of information, and I constantly find myself eager to see what you’ll uncover

next. Your dedication to excellence is apparent, and I anticipate that you’ll persist offering

such precious perspectives.

Your writing is a beacon in the sometimes turbulent waters of

online content. Your deep dives into a multitude of subjects are not only

informative but also immensely engaging. I appreciate the way you

balance meticulous investigation with narrative

storytelling, creating posts that are equally informative and engaging.

If there’s a method to subscribe your blog or join a

mailing list, I would be grateful to be informed

of your latest musings.

As a fellow writer, I’m motivated by the passion you pour into

each article. You have a knack for making

even the most complex topics approachable and intriguing.

The way you present ideas and link them to wider narratives is exceptionally skillful.

Please tell me if you have any workshops or e-books in the works, as I would be eager

to be guided by your expertise.

It’s uncommon to come across a blog that strikes the perfect chord with

both the intellectual and the personal. Your articles are written with a level of insight that

touches the core of the human condition. Whenever I visit your blog, I leave more informed and stimulated.

I’m keen to know whether you have plans to

When I started perusing your blog, I knew it was something

extraordinary. Your talent to delve into challenging

topics and demystify them for your audience is truly noteworthy.

Each post you publish is a repository of knowledge, and I always find myself anxious to discover what you’ll uncover next.

Your commitment to excellence is clear, and I anticipate that you’ll keep on providing such

invaluable perspectives.

Pingback: counseling san diego ca

This is my first time go to see at here and i am actually happy to read everthing at alone place.

10 Unexpected Pornstar Tips Porn Star – clicavisos.com.ar,

5 Killer Quora Answers To Adultwork Pornstar

Adultwork pornstar

What’s The Current Job Market For Pornstars On Playboy Professionals Like?

Pornstars On Playboy

10 Mobile Apps That Are The Best For Find Accident Attorney Accident Attorneys Nashville

Initially, it could be due to measurement error in reservation or accepted job attributes.

Here is my web page :: http://hackyourself.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=integramais.com.br%2F2024%2F04%2F18%2Fthe-importance-of-finding-the-right-job-dress-code%2F

Ten video blackjack tables can be played at BetNow, such as unique variations like surrender and double exposure.

Also visit my web blog; https://usafieds.com/author/melaineears/

Guide To Kayleigh Porn Star: The Intermediate Guide The Steps

To Kayleigh Porn Star kayleigh porn star

After looking over a handful of the blog articles on your

blog, I honestly appreciate your way of blogging.

I book-marked it to my bookmark website list and

will be checking back soon. Take a look at my web site too and let me know what you think.

10 Unexpected Find Accident Attorney Tips accident Attorneys Nyc

The No. Question That Everyone In Onlyfans Pornstars Needs To Know

How To Answer pornstars with onlyfans

Hello, Neat post. There’s an issue with your web site in web explorer, could check this?

IE nonetheless is the market leader and a big section of folks will pass

over your excellent writing due to this problem.

What’s The Reason Everyone Is Talking About Attorney For

Accident Claim Right Now accident attorney in Gainesville

We’re a group of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community.

Your site offered us with valuable info to work on. You’ve performed a formidable process and our whole group might be grateful to you.

The Reasons To Focus On Improving Accidents Attorney Near Me Accident attorney in gainesville

See What Kayleigh Porn Star Tricks The Celebs Are Utilizing kayleigh Porn Star

Right away I am going facebook vs eharmony to find love online do

my breakfast, afterward having my breakfast coming yet again to read

further news.

Could Accident Attorneys In My Area Be The

Key To 2023’s Resolving? determine

Mi web porno favorito es http://centroculturalrecoleta.org/blog/pages/c_digo_de_promoci_n_1.html

10 Tips To Know About Affordable Search Engine Optimisation Packages Uk affordable seo near me

5 Killer Quora Answers On Double Glazed Window Repairs Near Me double glazed window Repairs near Me

The Benefits Of Motor Vehicle Case At A Minimum,

Once In Your Lifetime Vimeo.Com

11 Methods To Completely Defeat Your Accident Claim

Oak Hill Accident Lawsuit

The 9 Things Your Parents Taught You About Asbestos Lawsuits

asbestos lawsuit (https://maps.google.com.ph/url?q=https://vimeo.com/704943188)

What The 10 Most Stupid Car Accident Litigation Mistakes Of

All Time Could’ve Been Prevented belle glade car accident lawsuit

Five Killer Quora Answers On Sleeper Couch With Storage sleeper couch with storage

(fsrauthserv.connectresident.com)

An dunn asbestos law firm (Vimeo.Com)

lawsuit can be a way for the victim or their family members to receive compensation from companies responsible for their

exposure. Compensation can be in the form a jury verdict or settlement.

Your Family Will Be Thankful For Having This Double Glazing

Repair Near Me Replacement double glazing windows

10 Healthy Idn Poker Habits spam

The 10 Most Terrifying Things About Dangerous Drugs Law Firms dangerous drugs law firm

You’ll Never Guess This Upvc Window Repair Near Me’s Benefits upvc Window Repair near me

Are You Sick Of Amazon Online Shopping Clothes Uk? 10 Inspirational Ideas To Revive Your Passion Oculus Quest Storage Case

20 Up-And-Comers To Follow In The Mesothelioma Victims Compensation Industry mesothelioma settlement Amounts

Where Are You Going To Find Double Glazing

Showrooms Near Me Be One Year From Now? Local Double Glazing Companies

Why Adding A Boat Accident Lawyer To Your Life Will Make All The Change farr

west boat accident attorney (https://vimeo.com/709548531)

See What Locksmiths Near Me For Cars Tricks The Celebs Are Using locksmith

What Is The Heck Is Boat Accident Litigation? Boat Accident Attorney

The Unspoken Secrets Of Trusted Online Shopping Sites For Clothes

Xsmall Therapeutic Hand Gloves

Medical Malpractice Lawsuit Tips From The Best In The Industry lawyer

The 12 Types Of Twitter Mesothelioma Attorney Accounts You Follow On Twitter Tell city

mesothelioma law firm (vimeo.com)

An In-Depth Look Back What People Said About Womens Rabbit Vibrators Sex Toy 20 Years Ago Adult Toys Rabbit

This Is A Guide To Pram Stores Near Me In 2023 pram shops Near me

10 Quick Tips For Upvc Window Repairs Upvc Windows repair

You’ll Never Guess This Shopping Online Uk To Ireland’s

Benefits Shopping Online Uk To Ireland

Watch Out: How Slot Demo Princess 1000 Is Taking

Over And What You Can Do About It demo slot pragmatic princess – Margarito,

Bisexual: The Ugly Real Truth Of Bisexual Camshow

The 10 Most Scariest Things About Double Glazing Company Near Me Double Glazing Company Near Me

(http://0522224528.Ussoft.Kr/G5-5.0.13/Bbs/Board.Php?Bo_Table=Board01&Wr_Id=943850)

15 Best Pinterest Boards Of All Time About CSGO Cases Explained snakebite

case (Freddie)

Three Reasons Why You’re Online Shop Is Broken (And How To Repair It) Vimeo

How To Explain Sbobet To A 5-Year-Old goblok

13 Things About Upvc Window Repairs You May Not Have Considered upvc window Repairs near me

Why You Should Concentrate On Improving Online Clothes Shopping Sites Uk Vimeo.com

15 Up-And-Coming Demo Slot Princess 1000 Bloggers You Need To Watch what time Are the Shows On princess cruises

The Benefits Of Asbestos Lawyer At The Very Least Once In Your Lifetime Asbestos claim

The 12 Most Popular Workers Compensation Legal Accounts To Follow On Twitter

Workers’ Compensation

10 Things Everyone Has To Say About Double Glazing Near Me Near by

25 Surprising Facts About Railroad Injuries Litigation railroad injuries lawyers (https://bindx.ai/en/go/Route?to=ahr0chm6ly92aw1Lby5jb20vnza4ndkymdk3)

The 10 Most Terrifying Things About Which Is Best For Online Grocery Shopping Which Is Best For Online Grocery Shopping

Guide To Childs Pram: The Intermediate Guide

In Childs Pram childs pram

Personal Injury Law: What’s No One Is Discussing personal Injury Attorney

Car Accident Case Tips From The Top In The Business car accident attorneys

The Main Issue With Cerebral Palsy Claim, And How

To Fix It Cerebral Palsy Lawyers

Repairs To Upvc Windows Tips To Relax Your Everyday LifeThe Only Repairs To Upvc Windows Trick That Every Person Must Know repairs to upvc Windows

Nine Things That Your Parent Teach You About Personal Injury Claim firms

The Most Powerful Sources Of Inspiration Of Trusted Online Shopping Sites

For Clothes bazic jeweltones ruler (https://vimeo.com/931313293)

11 Methods To Redesign Completely Your Replace Upvc Window Handle Repairs To Upvc Windows

The Reasons You Should Experience Double Glazed Replacement Glass Near Me At The Very Least Once In Your Lifetime

commercial

10 Things You Learned In Kindergarden Which Will Aid You In Obtaining Cerebral Palsy Lawsuit

Cerebral Palsy lawsuits

20 Myths About Birth Injury Attorney: Debunked Birth Injury Lawsuits

You’ll Never Guess This Upvc Window Repairs’s Tricks Upvc Window Repairs – Smartpeme.Depo.Gal –

What A Weekly Double Glazing Glass Replacement Near Me Project

Can Change Your Life double glazed Windows Cost

A An Instructional Guide To Mesothelioma Attorney From Start To Finish lincoln city mesothelioma law firm (Ilene)

Where Are You Going To Find CSGO New Case 1 Year From This Year?

cs20 case

20 Best Tweets Of All Time About Semi Truck Law

grafton semi truck accident Lawsuit

What The Heck What Is Birth Injury Attorney? madisonville birth Injury lawsuit

Automobile Locksmiths Near Me Tools To Ease Your Daily Life Automobile Locksmiths Near Me Trick Every Individual Should Be Able To automobile locksmiths near me

The Reasons To Work With This Injury Lawyers fayetteville injury Law Firm

Why You Should Focus On Enhancing Which Is The Best Online Supermarket

Main Access Ladders For Pools

The Most Innovative Things That Are Happening With Replacement Lock For Upvc Door upvc doors and windows

14 Cartoons About Motorcycle Accident Lawyer That’ll Brighten Your Day motorcycle accident attorney

5 Killer Quora Answers On L Shaped Couches For Sale

l shaped couches For sale

14 Businesses Doing An Amazing Job At Upvc Windows And Doors upvc windows repairs (maps.google.gl)

The No. 1 Question Everybody Working In Personal Injury Lawyer Should Know How To Answer lawsuits

4 Dirty Little Tips On Slot Demo Gratis Pragmatic Play No Deposit Industry Slot Demo Gratis Pragmatic Play

No Deposit Industry slot demo pragmatic terbaru

You’ll Never Guess This Best CSGO Case To Open’s

Tricks cs20 Case

Why Is Personal Injury Accident Attorneys So Famous? personal Injury lawyers miami

The Infrequently Known Benefits To Slot Demo Pragmatic demo games free pragmatic

How Auto Accident Lawsuit Has Become The Top Trend In Social Media Converse auto accident attorney

10 Private ADHD Test Strategies All The Experts Recommend Near Me

Where Do You Think Upvc Window Repairs 1 Year From Right Now?

upvc window repairs near Me

Are CSGO Skin Sites Legit 101″The Ultimate Guide For Beginners case Spectrum

Don’t Be Enticed By These “Trends” Concerning Mazda

3 Key Fob Mazda Key

Here’s A Little Known Fact Regarding Slot Demo Gratis Demo Slot Free

10 Things That Your Family Teach You About Mesothelioma mesothelioma (Angela)

10 Startups That Are Set To Revolutionize The Blown Double Glazing Repairs Near Me Industry For The Better repair double glazing windows [Lesli]

What Do You Know About Railroad Injuries Case?

green cove springs railroad injuries lawyer

You’ll Never Guess This Upvc Window Repair Near Me’s Secrets Upvc Window Repair (https://Desirerose.Com/Member/Login.Html?Nomemberorder=&Returnurl=Http://Olderworkers.Com.Au/Author/Brizt61Erus1-Gemmasmith-Co-Uk/)

How Veterans Disability Claim Rose To The #1 Trend In Social Media grove veterans disability lawyer

Why Mesothelioma Lawyer Is More Difficult Than You Imagine

Mesothelioma attorney

Responsible For The CSGO Cases Highest Roi Budget?

10 Unfortunate Ways To Spend Your Money operation phoenix weapon case (Zoe)

You cannot tell by just looking at something whether it’s

made of union city asbestos law Firm.

You cannot smell or taste it. Asbestos can only be identified when the materials

that contain it are broken, drilled, or chipped.

20 Insightful Quotes About Asbestos Legal asbestos claim (http://Www.technoplus.Ru)

The 12 Worst Types Online Shopping Uk For Clothes Tweets You Follow Pipe Unblocker gun

Double Glazing Glass Replacement Near Me 101: This Is The Ultimate

Guide For Beginners Replace double glazing glass

What’s The Job Market For 9kg Washing Machine Price Professionals Like?

9Kg Washing Machine Price

9 Things Your Parents Teach You About Peugeot 207 Car Key Peugeot 207 Car Key

What Experts In The Field Of Hyundai I10 Key Replacement Want You

To Know? hyundai accent key replacement

How To Save Money On Truck Accidents Attorneys Millersville Truck accident lawyer

20 Fun Details About Avon True Colour Glimmerstick Avon glimmersticks

How To Save Money On Online Shopping Sites For Clothes famous online shopping sites for

clothes (http://www.cobaev.edu.mx)

Why Everyone Is Talking About Injury Lawyer Right Now Injury Lawsuits

10 Facts About Injury Litigation That Will Instantly Put

You In A Good Mood firms

3 Ways That The CS GO Case Battle Will Influence Your Life Case Opening Website

Pingback: What Is CSGO Open Cases Sites And Why Is Everyone Dissing It? – Czardonations

The Top Accident Claim That Gurus Use Three

Things accident attorney [Burton]

20 Things That Only The Most Devoted Cheap Prams Fans Are Aware Of pushchairs

The Most Pervasive Problems In Online Shopping Clothes Uk Cheap Vimeo

20 Reasons Why Motorcycle Accident Settlement Will Never Be Forgotten vimeo

14 Cartoons About Combo Washer That Will Brighten Your Day washer dryer

– Utahsyardsale.com –

Guide To Double Glazed Window Near Me: The Intermediate Guide

The Steps To Double Glazed Window Near Me double glazed window Near Me

The majority of asbestos victims, as well as their families

start the process by retaining a skilled lawyer.

A qualified attorney will help the victims

prepare a suit to get compensation from defendants that made asbestos-containing products.

Also visit my site – Vimeo.com

Where Do You Think Veterans Disability Attorney

Be One Year From Now? Olean Veterans Disability Lawyer

Birth Injury Compensation: A Simple Definition Birth injury Attorney

8 Tips To Improve Your Kit Avon Game avon starter kit 2024 Uk

You’ll Be Unable To Guess Upvc Window Repair Near Me’s Tricks Upvc Window Repair Near Me (Hu.Feng.Ku.Angn.I.Ub.I.Xn–.Xn–.U.K37@Cgi.Members.Interq.Or.Jp)

Expert Advice On Car Locksmiths Near Me From An Older Five-Year-Old locksmith cars Near me

Are Play Poker The Best There Ever Was? must a nice

Guide To Uk Online Shopping Sites Like Amazon: The Intermediate Guide In Uk Online Shopping Sites Like Amazon uk online shopping sites like amazon [Camille]

A Guide To CS GO Weapon Case From Beginning To End Csgo Cases

15 Trends To Watch In The New Year Online Shopping Cheap online shopping uk Clothes

Pingback: 10 Myths Your Boss Has Regarding CS GO Case Battles – Czardonations

One Key Trick Everybody Should Know The One Leather Sleeper Sofa Trick Every Person Should Know Reversible sleeper sectionals

You’ll Never Guess This Birth Injury Case’s Secrets birth injury (Elma)

7 Essential Tips For Making The Most Out Of Your Replacement Double Glazed Glass Only Near Me repairs double

glazed windows (Anthony)

Why Auto Accident Attorney Isn’t A Topic That People Are Interested In. johnstown auto accident lawyer

16 Must-Follow Facebook Pages To Upvc Windows And Doors-Related Businesses repair Upvc window

9 . What Your Parents Taught You About What Is A Ghost

Immobiliser what Is a Ghost immobiliser

The History Of Private ADHD Assessment In 10 Milestones how much does a private adhd assessment cost

What’s The Current Job Market For Double Glazed Repairs Near Me Professionals

Like? double glazed repairs near me (Julissa)

A Comprehensive Guide To Cheap Online Grocery Shopping Uk.

Ultimate Guide To Cheap Online Grocery Shopping Uk best online shopping sites in uk For clothes

You’ll Never Guess This Online Clothes Shopping

Websites Uk’s Tricks Online clothes shopping websites uk

12 Companies That Are Leading The Way In Double Glazed Window Near Me Double glazed window Near me

Unexpected Business Strategies Helped Window Repair Near Succeed Upvc window repairs

The 10 Worst Asbestos Case Mistakes Of All Time Could Have Been Prevented asbestos lawsuit; Florine,

The Most Common Mistakes People Make With Car Accident Law Car Accident law firms

What Is It That Makes Car Accident Case So Famous?

car accident Law Firms

3 Reasons You’re Not Getting Auto Accident Lawyer

Isn’t Performing (And Solutions To Resolve It) Auto Accident Law

Firm – P3Terx.Com,

The One Boat Accident Lawyer Trick Every Person Should Be Able To pleasant garden boat accident lawsuit

Why You’ll Want To Read More About Latest Avon Brochure UK online Brochures

Need Inspiration? Look Up Erb’s Palsy Case Erb’s Palsy Lawyer

What Will Best Personal Injury Lawyer Be Like In 100 Years?

Personal injury lawyers san Diego

Demo Slot Starlight Princess 1000 Tools To Help You Manage Your Daily Lifethe One Demo Slot Starlight Princess 1000 Trick That Every Person Should Be Able To demo slot starlight princess 1000

Seven Explanations On Why Locksmith Near Me Car Is Important car locksmiths

[http://Www.40ikindi.com]

Ten Things You Learned In Kindergarden Which Will Aid

You In Obtaining Motor Vehicle Lawsuit Leesville motor Vehicle Accident attorney

The Reasons Online Shopping Sites Uk Could Be Your Next Big Obsession Cushioned Wool Hiker Socks

16 Facebook Pages You Must Follow For Cerebral Palsy Claim Marketers Cerebral palsy Law firms

ADHD Medication Titration Tools To Improve Your Everyday Lifethe Only ADHD Medication Titration Trick That Everyone Should Know adhd medication titration – http://www.diggerslist.com,

Indisputable Proof You Need Luton Door And Window damaged property for sale luton

The Most Profound Problems In Replacement Lock For Upvc Door upvc doors near me (glamorouslengths.com)

15 Lessons Your Boss Wished You Knew About Injury Legal ruidoso Injury law firm

5 Killer Quora Answers To Online Home Shop Uk Discount Code online Home shop uk discount

code (https://Ladder2leader.com)

You’ll Be Unable To Guess Convertible Sectional Sofa’s Tricks

convertible sectional sofa (Kit)

The Most Convincing Proof That You Need CS GO Cases To Open recoil case

5 Killer Quora Answers On Secondary Double Glazing Near Me double glazing near me (http://9d0bpqp9it2sqqf4nap63f.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=inquiry&wr_id=99375)

Windows And Doors Luton Tools To Ease Your Daily Life Windows And Doors Luton Trick That Every Person Must Know doors luton (Luella)

Five Killer Quora Answers On Medical Malpractice Attorneys medical Malpractice attorneys

Why You Should Focus On Improving Workers Compensation Compensation workers’ Compensation lawsuit

What’s The Job Market For Medical Malpractice Litigation Professionals Like?

medical Malpractice

Guide To Online Shopping Sites In United Kingdom: The Intermediate Guide In Online Shopping Sites In United Kingdom Online shopping sites In united Kingdom

The 10 Most Terrifying Things About Online Retailers Uk Stats online retailers uk Stats

10 Things You Learned In Kindergarden To Help You Get Started With Injury Attorney injury lawyers

15 Reasons You Shouldn’t Be Ignoring Welcome Kits welcome kit (txt.fyi)

20 Trailblazers Setting The Standard In Malpractice Compensation malpractice lawyer – Leigh –

20 Inspirational Quotes About Auto Accident Attorney Okeechobee Auto accident law firm

10 Joker123 Gaming Related Projects That Can Stretch Your Creativity spam

7 Things You Never Knew About Medical Malpractice Lawyers medical malpractice lawsuits

The 12 Worst Types Auto Locksmiths Accounts You Follow On Twitter auto key Smith

The Time Has Come To Expand Your Motor Vehicle Settlement Options

Motor Vehicle Accidents

15 Reasons Why You Shouldn’t Be Ignoring Online Shopping Sites For

Clothes Us Online Shopping Sites For Clothes

Why Is It So Useful? In COVID-19 upvc doors in luton (gwwa.yodev.net)

Could Truck Accident Lawyers Be The Key To Achieving 2023?

benton truck Accident law firm

Why People Are Talking About Replacement Upvc Door Handles Right Now Upvc Door Hinge Types

A Look At The Ugly The Truth About Auto Lock Smiths auto Locksmith cost

Starlight Princess Demo 101:”The Complete” Guide For Beginners slot starlight Princess demo

5 Killer Quora Answers To Double Glazed Window Repairs

Near Me double glazed window repairs near me

“Ask Me Anything”: Ten Answers To Your Questions About Semi Truck Attorney

firm

10 Things Everyone Hates About Car Accident Attorneys Car

Accident Attorneys car accident law firm; Kaitlyn,

10 Reasons You’ll Need To Be Educated About Adhd Medication Uk

medication for adults with add

5 Injury Claim Projects For Any Budget Hazel Crest Injury Lawyer

What’s The Job Market For Adult ADD Treatments Professionals?

Adult Add treatments

Are You Making The Most Of Your Washer Dryer Combo Brands?

washing Machines on Offer

You’ll Never Be Able To Figure Out This Private Psychiatrist

Sheffield Cost’s Tricks private psychiatrist sheffield

Why Is Ghost Immobiliser So Effective In COVID-19 ghost 2 immobiliser fitting Near me

Ask Me Anything: 10 Answers To Your Questions About Auto Locksmiths Mobile Automobile Locksmith Near Me

16 Must-Follow Facebook Pages To Upvc Windows And Doors-Related Businesses Upvc Windows repair near Me

What NOT To Do With The Best Car Accident Attorney Industry Top car accident Attorney

9 . What Your Parents Teach You About Pushchair

Car Seat Pushchair Car seat

5 Laws That Can Help The Pushchair Industry Pushchairs And Prams

20 Myths About Double Glazed Repairs Near Me: Dispelled misted double glazing

See What Online Shopping Stores In London Tricks The Celebs Are Using Online Shopping Stores In London (M.Simeun.Com)

How Mesothelioma Legal Can Be Your Next Big Obsession Mesothelioma Claim

11 Ways To Completely Revamp Your Auto Accidents Attorneys auto accident lawyer houston

How Do I Explain Auto Accident Lawyer To A Five-Year-Old vehicle

Five Motor Vehicle Lawyer Lessons From Professionals Vimeo.Com

10 Unexpected CSGO Cases Opening Tips gamma case

How To Save Money On Cheap Squirting Dildos sale

The Best Advice You’ll Receive About Bukkake Blow

See What Online Shopping Stores In London Tricks The Celebs Are Using online shopping stores

in london (Boris)

How To Outsmart Your Boss With Locksmith For Auto Auto Keys Locksmith

What Is The Double Glazing Installers Near Me Term And How To

Utilize It Repairs to double glazing windows

What Is The Reason Replacement Mazda Key Is Right For You?

Mazda 2 Key Replacement

Nine Things That Your Parent Taught You About Online Shopping Sites Clothes Cheap

online shopping sites clothes cheap

10 Best Mobile Apps For Symptoms Of Adhd In Adults Uk Adhd symptoms Female adults

Ten Myths About Window Repair Near That Aren’t Always True upvc window repair Near me

You’ll Never Guess This Adult Female Adhd Symptoms’s Benefits female adhd symptoms [http://www.stes.tyc.edu.tw/]

Ten Things You Learned In Kindergarden That Will Help

You With CSGO New Case Case horizon

How You Can Use A Weekly Personal Injury Claim Project Can Change Your Life Personal injury law firms

The Unspoken Secrets Of Window Repair Near window Repair near Me

Do Not Forget Marc Jacobs Bag Tote: 10 Reasons Why You No Longer Need It marc jacobs bags tote

A Provocative Rant About Upvc Windows And Doors Upvc windows repair

Responsible For The Replace Upvc Window Handle Budget? 12 Top Notch

Ways To Spend Your Money Repairs to upvc windows

Who Is The World’s Top Expert On Which Online Stores Ship Internationally?

Buy monroe 271662r Strut

10 Things Everyone Has To Say About Upvc Window Locks Upvc Window Locks upvc window repairs

The Best Advice You Can Receive About Private Mental Health Assessment London Assessment for mental health

10 Facts About 18 Wheeler Wreck Lawyers That Make You Feel Instantly A Good Mood 18 wheeler accident lawyers

Waters Kraus and Paul’s mesothelioma lawyers hold asbestos-related companies accountable for their role in creating

exposure to bellevue asbestos Law firm and asbestos-related

diseases.

How To Determine If You’re Prepared To Go After CS GO Case New winter offensive weapon case [Brendan]

Why People Are Talking About Michael Kors Handbags Sale Today Kors

Michael handbag (extension.unimagdalena.edu.Co)

5 Killer Quora Answers To Beko Washing Machine New Beko washing Machine new

4 Dirty Little Details About Upvc Windows Repair And The Upvc Windows Repair Industry repair

upvc windows (alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.bn)

The 10 Scariest Things About List Of Online Shopping

Sites Uk List Of online shopping sites uk

Don’t Make This Mistake You’re Using Your Car Accident Litigation Vimeo.Com

5 Cliches About Pvc Window Repairs You Should Stay Clear Of Door

Five Killer Quora Answers To Double Glazed Near Me double Glazed near me

Guide To Online Shopping Uk Cheap: The Intermediate Guide For Online Shopping Uk Cheap online shopping Uk cheap

9 . What Your Parents Teach You About Best Online Shopping Sites London best online

shopping sites london (Opal)

Beware Of These “Trends” Concerning Mesothelioma Lawsuit Mesothelioma Legal Assistance

10 Ass Tricks Experts Recommend Spy

20 Myths About Upvc Windows Repair: Dispelled Repair upvc windows

5 Killer Quora Answers To Birth Injury Attorney

Las Cruces Nm Birth Injury Attorney las cruces Nm

20 Inspiring Quotes About Malpractice Attorneys Malpractice Law Firms

You’ll Never Guess This Mesothelioma Financial Compensation’s Tricks mesothelioma Financial compensation

The 9 Things Your Parents Teach You About Upvc Window Repairs upvc window repairs

12 Companies That Are Leading The Way In Injury Litigation injured

15 Top Twitter Accounts To Find Out More About Dangerous Drugs Law Firms dangerous drugs lawsuits

The Guide To Replacement Double Glazed Glass Only Near

Me In 2023 Double Glazed Glass

How Online Charity Shop Uk Clothes Arose To Be The Top Trend In Social

Media Easy assembly bookshelf; vimeo.com,

20 Questions You Need To ASK ABOUT Comfortable Couches For Sale Before Purchasing It Most Comfortable Couch

20 Reasons Why Personal Injury Case Will Never Be Forgotten glenview personal Injury Lawyer

10 Slot Demo Starlight Princess No Lag Hacks All Experts Recommend slot demo Starlight princess 1000x

A Glimpse Into Motor Vehicle Lawyers’s Secrets Of

Motor Vehicle Lawyers Motor Vehicle Accident Attorney

10 Semi Truck Lawyer Tips All Experts Recommend Semi truck accident attorneys

Why Everyone Is Talking About Best 18 Wheeler Accident Attorney Right Now

Vimeo

The 10 Most Terrifying Things About Online Shopping Stores List online shopping Stores List

The No. One Question That Everyone Working In CSGO Cases Highest

Roi Should Be Able Answer snakebite Case, –7sbacdhoeojc1a3Amf1e6f.рф,

The Most Worst Nightmare About Mens Sex Toy It’s

Coming To Life Topsadulttoys.Uk

The People Who Are Closest To Birth Defect Lawyers Uncover Big Secrets Birth Defects

This Week’s Most Popular Stories About Birth Injury Attorney Iowa Birth Injury

Attorney Iowa Queens Birth Injury Attorney

7 Secrets About Window Repair Near That No One Will Tell You

window Repair near me

10 Kit Avon That Are Unexpected Avon kit; http://www.eurasiasnaglobal.com,

7 Tricks To Help Make The Most Out Of Your Online Shopping Sites List For Clothes Helios Light Controller With Timer

20 Trailblazers Leading The Way In Private

Mental Health Treatment mental Health assessments online

5 Mobile Slots Myths You Should Avoid real casino slots (https://www.buyandsellreptiles.com/author/kandispring)

10 Websites To Help You Become An Expert In CS GO New Cases Cs20 case

See What ADHD Tests Tricks The Celebs Are Making Use Of adhd test (Shenna)

The Reasons You Shouldn’t Think About Improving Your Injury Litigation Big Rapids Injury Law Firm

One Key Trick Everybody Should Know The One Dangerous Drugs Trick Every Person Should Be

Aware Of Vimeo

Unexpected Business Strategies For Business That Aided Window Repair Near Achieve Success upvc Window repairs

What Is Online Jobs Work From Home No Experience And Why Is Everyone Speakin’ About It?

work from home jobs that Are easy

The Top Companies Not To Be Monitor In The Online Shopping Sites For Clothes Industry Famous online shopping Sites for clothes

This Is A Guide To Asbestos Lawyer In 2023 Asbestos legal

What Is Reallife Sexdolls And How To Use What Is Reallife Sexdolls And How To Use sex doll price [Elden]

10 Unexpected Motorcycle Accident Lawyer Tips delano Motorcycle Accident law firm

15 Best Dangerous Drugs Law Firm Bloggers You Should Follow delavan dangerous drugs lawsuit

See What Double Glazed Windows Near Me Tricks The Celebs Are Making Use Of

double glazed windows near Me

Although berkeley asbestos law firm is still banned,

several incremental legislative proposals have been tossed around Congress.

One of these, the Frank R.

Everything You Need To Be Aware Of Asbestos Case Asbestos Litigation

The 10 Scariest Things About Dangerous Drugs Attorney attorney

16 Facebook Pages That You Must Follow For Mesothelioma Lawsuits-Related Businesses

the village mesothelioma law firm

25 Shocking Facts About Heat-Pump Tumble Dryer Heat Pump Tumble Dryers (https://Muabanthuenha.Com)

Three Common Reasons Your CSGO Cases Explained

Isn’t Working (And The Best Ways To Fix It) chroma 2 case (Herbert)

The 3 Greatest Moments In Psychological Assessment Near

Me History Adhd psychiatrist Assessment

10 Facts About Medical Malpractice Lawyer That Can Instantly Put You In An Optimistic Mood medical malpractice law firm (Leola)

A Retrospective: How People Talked About Auto Ghost Immobiliser 20 Years Ago

Ghost Immobiliser 2

10 Things That Your Competitors Inform You About Online Casino goblok

Why Is Everyone Talking About Repair Window Right Now Window Replacement Near Me

10 Websites To Help You Be A Pro In Hire Car Accident Lawyers

houston car accident Attorneys

Buzzwords De-Buzzed: 10 Other Ways To Say Replacement Double Glazing Units Near Me Double Glazing unit

20 Fun Details About Double Glazed Window Repairs Near Me double glazing repair

Near me (dnpaint.co.kr)

Three Reasons Why Your Double Glazing Windows Repair Is Broken (And How

To Fix It) upvc repairs Near Me

Is Dangerous Drugs Lawyers The Best There

Ever Was? Vimeo.Com

5 Laws That’ll Help The Railroad Injuries Compensation Industry railroad injuries law firms, Josef,

5 Killer Quora Answers To Best Online Shopping Websites Uk Best Online Shopping Websites Uk

20 Resources That Will Make You More Efficient At Mesothelioma Attorney Burr Ridge mesothelioma lawsuit

10 Best Books On Window Repairs upvc window repairs

The People Closest To Railroad Injuries Lawyers Share Some

Big Secrets bennettsville railroad Injuries law Firm

10 Real Reasons People Dislike Erb’s Palsy Claim Erb’s Palsy Claim erb’s palsy Law firm

10 Things Everyone Has To Say About Auto Accident Compensation Auto Accident Compensation Lawyers Auto accident (urlki.Com)

5 Laws That Can Help The Double Glazed Windows Near Me Industry

double glazed windows near me

How To Identify The CSGO Open Cases Sites Right For You gaming

Five Killer Quora Answers On L Shaped Sleeper Sofa l shaped Sleeper Sofa

Why We Love Birth Injury Attorney (And You Should, Too!) injuries

The Most Significant Issue With Online Shopping And How To Fix It

80w strobe light Bar

Repair Misted Double Glazing Near Me Techniques To Simplify Your

Everyday Lifethe Only Repair Misted Double Glazing Near

Me Trick That Every Person Must Learn double glazing Near me

5 Killer Quora Answers On Tumble Dryer With Heat Pump Tumble Dryer With Heat Pump

10 Inspirational Graphics About Workers Compensation Law workers’ Compensation Attorney

14 Cartoons About Birth Defect Claim To Brighten Your Day defects

It’s The Evolution Of Medical Malpractice Compensation medical Malpractice Lawyers

What Is Private Psychiatrist Assessment And Why You Should

Be Concerned cost of private psychiatrist; karateorchid2.bravejournal.net,

12 Companies Are Leading The Way In Citroen Key

Fob reprogramming

How To Build Successful Ghost Installations Guides With Home installing ghost immobiliser

The Guide To Personal Injury Lawsuit In 2023 personal injury attorney (Melodee)

11 Methods To Completely Defeat Your CS GO New Cases Cs20 Case (http://Www.Google.Com)

15 Unexpected Facts About Auto Collision Lawyer That You Never Knew car accident law firm

Test: How Much Do You Know About Citroen C1 Key

Replacement? Citroen Key Fob Repair

5 Car Accident Lawyers Lessons From The Professionals kermit car Accident Attorney [https://vimeo.com/707174883]

Shopping Online: What No One Is Discussing vimeo.com

What’s The Current Job Market For Online Shopping Uk For

Clothes Professionals Like? Online Shopping Uk For Clothes, http://Chronocenter.Com,

10 No-Fuss Strategies To Figuring Out Your Repairs To Upvc

Windows Upvc window Repair

The Most Hilarious Complaints We’ve Seen About Malpractice Lawsuit

malpractice Lawsuits

It’s True That The Most Common Double Glazed Window Near Me Debate Isn’t As Black

And White As You Might Think Double Glazed Window Near Me

The Expert Guide To Double Glazing In Luton windows

See What Bmw Car Key Cover Tricks The Celebs Are Utilizing bmw car key Cover

5 Laws Anybody Working In Beco Washing Machine Should Know beco washing Machines (mariskamast.net)

Who’s The Top Expert In The World On Dangerous Drugs Law Firms?

dubuque dangerous drugs lawyer (vimeo.com)

There’s A Good And Bad About Private ADHD Diagnosis private Assessment adhd

20 Trailblazers Lead The Way In Online Shopping Sites In Uk For Electronics Uv400 Protection Sunglasses

5 Killer Quora Answers On Window And Door Replacement

London window and door replacement london

15 Up-And-Coming Workers Compensation Compensation Bloggers You Need

To Follow Workers’ Compensation Lawsuit

The Most Common Double Glazed Units Near Me Mistake Every

Beginning Double Glazed Units Near Me User Makes replacement double glazed units

near me (Arthur)

You’ll Be Unable To Guess Private Adhd Assessment Near

Me’s Tricks private adhd assessment near me (Tiffani)

A Look Into The Secrets Of Cum Indian-Bhabhi

5 How To Ship To Ireland From Uk Lessons Learned From

The Professionals Kids Sports Sandals

Guide To Veterans Disability Compensation: The Intermediate Guide For Veterans

Disability Compensation Veterans Disability

16 Must-Follow Instagram Pages For Double Glazing In Luton-Related Businesses upvc windows near me

(Parthenia)

What Experts From The Field Of Mesothelioma Claim Want You To Know?

Destin Mesothelioma lawyer

7 Simple Secrets To Totally Rocking Your Accident Lawyers

Panama City Accident Injury Law Firm

5 Laws Anybody Working In Mesothelioma Should Be Aware

Of Mesothelioma Attorney

This Week’s Top Stories Concerning Car Accident Lawyer car accidents

Where Will Erb’s Palsy Claim Be 1 Year From This Year? erb’s palsy law firm

Why Adult Video Isn’t A Topic That People Are Interested In Adult Video

Stretch

Why You Should Be Working With This Diagnostics Automotive diagnostic check – Alta –

Where Is Online Shopping Be 1 Year From Today?

Sequin Wall Panel

See What Avon Become Representative Tricks The Celebs Are Utilizing

become a Representative makeup (gwwa.yodev.net)

What’s The Job Market For Motorcycle Accident Attorney Professionals Like?

motorcycle accident Attorney

Are You Responsible For A Washer Dryer Combos Budget?

12 Top Ways To Spend Your Money Cheap Washer Dryer Combos

10 Tips For Injury Lawyers That Are Unexpected franklin lakes injury lawyer

It Is A Fact That Best Adhd Medication For Adults With Anxiety

Is The Best Thing You Can Get. Best Adhd Medication For Adults With Anxiety Add Medication Adult

Why You Should Focus On Improving Cheap Online Grocery Shopping Uk Professional Cable Railing Crimper

10 Erroneous Answers To Common CS GO Weapon Case Questions: Do You Know The Right Answers?

Esports 2013 case

10 Of The Top Facebook Pages Of All-Time About Upvc Window Locks upvc Windows repair

9 . What Your Parents Teach You About Upvc Window Repairs Near Me Window Repairs Near Me

Guide To Double Glazed Units Near Me: The Intermediate Guide

For Double Glazed Units Near Me double glazed units near Me

Railroad Injuries Settlement Tools To Ease Your Daily Lifethe One Railroad

Injuries Settlement Trick That Every Person Should Be Able To railroad Injuries

Slot Demo Gratis: The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly demo slot Koi Gate

The 10 Scariest Things About Upvc Windows Repairs

Upvc Windows Repairs (https://Engberg-Snyder.Thoughtlanes.Net/10-Instagram-Accounts-On-Pinterest-To-Follow-Double-Glazed-Repair)

10 Online Shopping Websites Clothes-Related Projects That Stretch Your

Creativity online shopping Websites for Clothes

A Peek Into Double Glazed Units Near Me’s Secrets Of Double Glazed Units Near

Me Double Glazed units

How To Determine If You’re In The Right Place To Case Opening Simulator CSGO Case gamma

The 10 Scariest Things About Birth Defect Attorneys Birth Defect

20 Reasons To Believe Avon Far Away Perfume Cannot

Be Forgotten avon today perfume – Karma,

How Online Charity Shop Uk Clothes Rose To The #1 Trend On Social Media 13

To 27 Inch Monitor Stand (https://Vimeo.Com/932210200)

15 Gifts For The Bdsmty Lover In Your Life Livesex

Are You Making The Most From Your Will CSGO Cases Go Up In Price?

cs2

The Biggest Issue With Upvc Replacement Door Handles, And What You Can Do

To Fix It door Panels upvc

In accordance with statutes which are referred to as statutes, asbestos victims

have only a short time in which they are able to file a lawsuit.

my web blog: Vimeo.Com

How Much Can Car Locksmith Near Me Experts Earn? Locksmith For Car Key Near Me

10 Healthy Online Shopping Websites Clothes Habits Best Luxury Online Shopping Sites Uk

The 10 Most Terrifying Things About Avon Skin So

Soft Where To Buy Avon skin so soft Where to buy

The 9 Things Your Parents Teach You About Upvc Window Repair Upvc window repair

10 Things We All Do Not Like About CSGO Most Profitable Cases operation wildfire case (Kraig)

Auto Accident Lawyer For Hire The Process Isn’t As Hard As You Think automobile accident Lawyer houston (umpda.um.edu.my)

5 Killer Quora Answers To Dangerous Drugs Law Firm

Dangerous Drugs

The No. 1 Question That Anyone Working In Counterstrike Ps5 Should Be Able To Answer

Gloves Cases

10 Things We Hate About Boat Accident Attorneys Harvard Boat accident lawsuit

15 Unexpected Facts About Play Casino Slots You Didn’t Know rainbet

17 Reasons Why You Should Ignore Double Glazing Near Me Double Glaze

The 10 Scariest Things About Situs Alternatif Gotogel situs alternatif Gotogel

It’s The Myths And Facts Behind Private Psychiatrist

Surrey Private Psychiatrist Uk Cost

See What Rv Sofa Sleeper Tricks The Celebs Are Utilizing rv

Sofa sleeper (playclip.Co.kr)

The 10 Scariest Things About Cheapest Online Grocery Shopping Uk Cheapest Online Grocery Shopping Uk

See What Online Charity Shop Uk Clothes Tricks The Celebs Are

Utilizing Online Charity Shop Uk Clothes

See What Repair Upvc Windows Tricks The Celebs Are Using repair upvc Windows

20 Semi Truck Lawyer Websites Taking The Internet By Storm union grove Semi truck accident law firm

8 Tips For Boosting Your Window Repair Luton Game door Repair

Why We Do We Love Hyundai Key (And You Should, Too!) hyundai Remote key replacement

If you’re diagnosed with mesothelioma, or any other

asbestos-related illness the lawyer you choose to work with will file legal claims against responsible

parties. They may choose to settle the matter or proceed

to trial.

Look at my website; Vimeo

How To Explain Mesothelioma Lawsuit To Your Grandparents Mesothelioma lawsuits

24-Hours To Improve Upvc Windows And Doors repair upvc Window

What’s The Reason You’re Failing At Uk Online Shopping

Sites For Electronics Vimeo

A An Instructional Guide To Semi Truck Lawyer From Start To Finish vimeo

You’ll Never Guess This Trusted Online Shopping Sites For Clothes’s Tricks Trusted Online Shopping Sites For Clothes

10 Replacement Double Glazed Glass Only Near Me That Are Unexpected double Glazed Glass

See What Can I Buy From A Uk Website Tricks The Celebs Are

Using can i buy from a uk website

14 Smart Ways To Spend Leftover Injury Litigation Budget Vimeo

Five People You Need To Know In The Designer Handbags And

Purses Industry Designer Handbags Popular

The History Of Car Accident Settlement car Accident Lawsuit

See What Treadmill For Sale Near Me Tricks The Celebs Are

Using treadmill for sale near me (Deb)

The 10 Most Scariest Things About Auto Accident Attorneys auto accident

From The Web: 20 Fabulous Infographics About Demo Princess

princess pragmatic play

How To Design And Create Successful CSGO Case New How-Tos And Tutorials To Create Successful CSGO Case New Home Bravo Case

Do You Know How To Explain Best Online Jobs Work From Home To Your

Boss people

15 Top Pinterest Boards Of All Time About Upvc Window Repairs upvc Window repairs Near me

Why Do So Many People Want To Know About Skoda Car Key Replacement?

Skoda Find My Keys – Toolbarqueries.Google.Com.Et –

The 10 Scariest Things About Upvc Windows Repairs

Upvc Windows Repairs, https://Www.17Only.Net/,

Indisputable Proof Of The Need For Windows Repairs Near Me emergency

10 Things Everyone Hates About Truck Accident Attorney For Hire trucking Accident Legal team

Michael Kors Handbags Black: A Simple Definition michael kors bag White

Five Laws That Will Aid Industry Leaders In Car Accident

Attorney Industry Braidwood car Accident law firm

See What Car Accident Lawsuit Tricks The Celebs Are Using Car Accident

What’s The Current Job Market For ADHD Titration Waiting List Professionals Like?

adhd titration waiting list

10 Things We All Were Hate About Asbestos Litigation Asbestos Settlement

20 Things You Should To Ask About Akun Demo Slot Before Purchasing It akun demo gacor

Are You Sick Of Asbestos Case? 10 Inspirational Sources That Will

Revive Your Passion Asbestos Claim

See What Replacement Car Key Audi Tricks The Celebs Are Using replacement car key audi

An wilmington Asbestos attorney lawsuit is a way for a victim and their family members to get

compensation from the companies that caused their exposure.

Compensation can take the form a jury verdict, settlement or a settlement.

Birth Injury Litigation: The Evolution Of Birth Injury Litigation ripon birth Injury Lawsuit

Windows And Doors Luton Tools To Improve Your Daily Lifethe One Windows And Doors Luton Trick That Everyone Should Be Able To windows and doors luton (https://dorfmine.com/proxy.php?link=http://netvoyne.ru/user/smellheart73/)

A Productive Rant About Malpractice Legal Clarendon hills malpractice lawyer

Where Do You Think Prada Bag For Men Be One Year From In The Near Future?

Near

Five Killer Quora Answers On Seat Leon Key Fob Replacement seat leon key fob

Guide To Uk Online Shopping Sites Like Amazon: The Intermediate

Guide On Uk Online Shopping Sites Like Amazon Uk Online Shopping Sites Like Amazon

What Is BMW Battery Replacement Key? To Utilize It bmw series 1 key

3 Ways In Which The Double Glazed Windows Repair Near Me Will

Influence Your Life handle For double glazed window (m.Ododo.Co.kr)

10 Startups That Will Change The Double Glazing Firms Near Me Industry For The Better window

Why We Our Love For CSGO Cases To Invest In (And You Should, Too!) Danger Zone Case

This History Behind Medical Malpractice Lawyers Can Haunt You Forever!

searcy Medical malpractice lawsuit

What’s The Current Job Market For Small Sleeper Couch Professionals Like?

Small Sleeper couch

10 Quick Tips To Motor Vehicle Case motor vehicle accident Law firms

A Guide To Repair Upvc Windows From Start To Finish Upvc Windows Repair

The 10 Most Terrifying Things About Treadmill UK Treadmill Uk

25 Shocking Facts About Top Mesothelioma Attorneys utica mesothelioma attorney

Everything You Need To Know About Heat Pump Tumble Dryer

Uk Heat pump tumble Dryers

What’s The Job Market For Designer Handbags Brown Professionals Like?

Designer Handbags Brown

Boat Accident Law The Process Isn’t As Hard As You Think Boat Accident Attorney (Minimalwave.Com)

Why Auto Accident Settlement Is The Next Big

Obsession Beloit Auto Accident Law Firm

14 Misconceptions Commonly Held About Online Home Shop Uk

Discount Code Interior Glass Bifold Door (Simone)

How Much Do Repair Upvc Windows Experts Earn? repairing upvc Windows

5 Killer Quora Answers To Replacement Double Glazing Units Near Me replacement double glazing units near me (Dorris)

Expert Advice On Upvc Windows And Doors From A Five-Year-Old

upvc windows repair (https://beasley-rode.federatedjournals.com/11-Faux-pas-that-actually-are-okay-to-make-with-your-double-glazed-window-repair)

15 Things You’ve Never Known About Ford Keys Cut Ford Car Keys Replacement

14 Smart Ways To Spend Leftover CSGO Battle Case Budget Offensive Weapon

The Ultimate Glossary Of Terms About Car Accident Compensation car accident law firm

Guide To Link Daftar Gotogel: The Intermediate Guide Towards Link Daftar Gotogel link daftar Gotogel

10 Websites To Help You Learn To Be An Expert In Repairs To Upvc Windows Upvc Repair

Is Your Company Responsible For The Ferrari Ghost Installer Budget?

12 Top Notch Ways To Spend Your Money Porsche 911 ghost installer

Treadmill: It’s Not As Expensive As You Think Treadmills Sale uk

Think You’re Ready To Start Doing CSGO Most Profitable

Cases? Try This Quiz broken fang case; Iesha,

The No. One Question That Everyone Working In Medical Malpractice Lawsuit Must Know How To Answer medical malpractice law Firms

Online Shopping Sites List For Clothes Tools To Help You Manage Your Daily

Lifethe One Online Shopping Sites List For Clothes Trick That Every Person Must Know Online shopping sites list for clothes

The Unspoken Secrets Of Boat Accident Lawyers Boat accident law firm

Twenty Myths About Birth Defect Litigation: Busted birth Defect attorneys

Don’t Buy Into These “Trends” About Mini Cooper Key Fob Replacement replacement mini cooper key

Don’t Buy Into These “Trends” About Birth Defect Lawsuit defects

The 3 Biggest Disasters In Truck Accident Lawyers For Hire

The Truck Accident Lawyers For Hire’s 3 Biggest Disasters In History Vimeo.Com

20 Insightful Quotes On Double Glazing Repairs Near Me window Replacement near Me

The Three Greatest Moments In Double Glazed Windows

Repair History Window Replacement

14 Cartoons About Personal Injury Claim That’ll Brighten Your Day lawyer

Upvc Door Repairs Near Me Tools To Improve Your Daily Life Upvc Door Repairs Near Me Trick Every Person Should Know Upvc door repairs near me

Why You Should Be Working On This Window Repair Near Upvc repair

10 Things Everyone Has To Say About CS GO New Cases CS GO

New Cases gamma case – https://mohs.gov.mm/docs?url=http://test.gitaransk.ru/user/leafself8/ –

Seven Explanations On Why Demo Slot Is So Important slot demo

idn [https://www.pcwanli.com/]

You’ll Never Be Able To Figure Out This Amazon Online Grocery

Shopping Uk’s Tricks amazon online grocery shopping

uk – Margret –

Five Lessons You Can Learn From Brochure Avon UK avon uk brochure

(Cole)

Become An Avon Rep Uk: What No One Is Discussing become an avon rep

uk, Valorie,

The Most Prevalent Issues In Adult ADD Treatment Nearby

Say “Yes” To These 5 Replacement Upvc Window Handles Tips upvc window repairs

10 Facts About Asbestos That Will Instantly

Put You In The Best Mood Asbestos Lawsuit

Do You Think Birth Injury Lawsuit Be The Next Supreme Ruler Of

The World? Birth Injury Law Firms

Buzzwords De-Buzzed: 10 Different Ways To Say CS GO Cases To Open operation broken fang Case

Why Do So Many People Are Attracted To Birth Injury Lawyers?

Birth Injury attorney

Are You Getting Tired Of Mesothelioma Lawsuits?

10 Inspirational Sources To Bring Back Your

Love reputable asbestos Attorney

5 Killer Quora Answers On Auto Accident Attorneys

Auto accident

The EPA prohibits the production, importation, processing and distribution of most asbestos-containing items.

However, some asbestos-related claims remain on court dockets.

My web site … Vimeo

Ten Things You Learned At Preschool, That’ll Aid You In Auto

Accident Compensation gering auto accident law Firm

5 Killer Quora Answers On Malpractice Attorneys

Malpractice

Searching For Inspiration? Try Looking Up Labor

Day Couch Sales gray couch living room [https://sextonsmanorschool.com/]

20 Things You Should Know About Charity Shop Online Clothes

Uk installerparts cat6 10 pack

5 Birth Defect Case Lessons From The Professionals lawyer

Birth Injury Case Tools To Help You Manage Your Everyday Lifethe Only Birth Injury Case Trick That

Should Be Used By Everyone Know birth Injury

What’s The Current Job Market For Double Glazed Repairs Near Me Professionals Like?

Double Glazed Repairs Near Me

15 Strange Hobbies That Will Make You Smarter At

Erb’s Palsy Law erb’s palsy Attorneys

20 Resources That Will Make You Better At Birth Injury Litigation East orange birth injury attorney – vimeo.Com –

See What Amazon Uk Online Shopping Clothes Tricks The Celebs Are Utilizing amazon uk online shopping clothes, Mikayla,

11 “Faux Pas” That Are Actually OK To Make With Your Citroen C3 Key Fob Citroen Xsara Picasso Key Fob (Gurye.Multiiq.Com)

A Provocative Remark About Upvc Window Repairs Window Repairs Near Me

Check Out What Veterans Disability Lawsuit Tricks

Celebs Are Using Veterans disability law firm

11 Strategies To Completely Redesign Your Dangerous Drugs Law Firm sanger dangerous Drugs lawyer (https://vimeo.com/709831889)

20 Things You Need To Know About Best Slot Payouts Hacksaw gaming Slot machines

Pingback: Slot Updates Explained In Fewer Than 140 Characters – LuxuriousRentz

Guide To Treadmill Best: The Intermediate Guide For Treadmill Best Treadmill best

10 Simple Steps To Start The Business Of Your Dream Anal

Business naughty

Walking Desk Treadmill: What’s The Only Thing Nobody Is Discussing machines

The 10 Most Scariest Things About List Of Online Shopping Sites In Uk list

of online shopping sites in uk (Lavada)

5 Killer Quora Answers On ADHD Titration UK Adhd Titration Uk

5 Must-Know Practices For Adhd In Adults Symptoms Test In 2023 adhd symptoms test (Kit)

24 Hours To Improve Demo Slot akun demo slot Pg

Window Repair Near Me Tools To Help You Manage Your Daily Lifethe One Window Repair Near Me

Trick Every Person Should Learn window repair near me

The 10 Most Scariest Things About Case Opening Sites CSGO Case Opening

9 Things Your Parents Teach You About Mesothelioma Compensation mesothelioma

What To Focus On When The Improvement Of Asbestos Attorney Asbestos case

How To Create Successful Double Glazed Front Doors Near Me Tutorials From Home double glazed front Door

7 Practical Tips For Making The Most Of Your Double Glazing Door Repairs Near Me double glazed window suppliers near

Me, http://www.Mazafakas.Com,

So , You’ve Bought Birth Injury Legal … Now What? Vimeo.Com

The Main Issue With Treadmill For Sale Near Me And How You Can Resolve It Accessories home

7 Secrets About Dangerous Drugs Lawyers That No One Will Tell You harrisonville dangerous Drugs attorney

Upvc Windows Near Me Techniques To Simplify Your Daily Life Upvc Windows Near Me Technique Every Person Needs To Be Able To Upvc Windows near me

Demo Slot Starlight Princess 1000 Tools To Streamline Your Everyday

Lifethe Only Demo Slot Starlight Princess 1000 Trick That Every Person Must Know demo slot starlight princess 1000

Guide To Slot Demo Princess 1000: The Intermediate Guide In Slot Demo Princess 1000 Slot demo princess 1000

The 10 Most Terrifying Things About Online Shopping Stores List

online Shopping stores list

A Comprehensive Guide To Designer Handbags Large.

Ultimate Guide To Designer Handbags Large Designer handbags london

10 Meetups On Veterans Disability Attorney You Should Attend chicago veterans disability lawsuit

Technology Is Making Glass Anal Butt Plugs Better

Or Worse? anal plugs – Deborah –

At its height, chrysotile was responsible

for 99% of the charleroi Asbestos Attorney produced.

It was used by many industries, including construction, fireproofing, and insulation.

A Guide To All CSGO Skins From Beginning To End Gamma 2 Case

10 Facts About Couches Sale That Can Instantly Put You In An Optimistic Mood Cheap Sectionals for sale

10 No-Fuss Methods For Figuring Out Your Online Slots hacksaw

online slots (cse.Google.pl)