Motor learning in judo: From basics to expertise

In his latest blog post, Garmt explored some of the science behind motor learning in judo, from the foundational stages to expertise. The post offers insights into how coaches and athletes can innovate training to train smarter, more adaptive judoka.

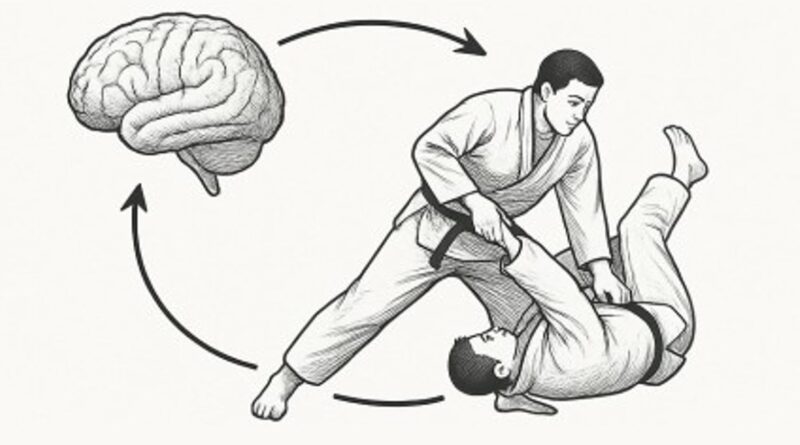

Motor learning is the complex process through which people develop new movements and skills. This process involves connections between various brain areas and learning mechanisms and is essential for mastering sport techniques like judo. Although learning a complex skill, such as becoming a top judoka, can take thousands of hours, studies on motor learning tasks can provide important insights into the fundamentals of motor learning.

Core components of motor learning

Motor learning is a continuous and dynamic process based on three interconnected components:

- Setting the movement goal: The process begins with determining the desired outcome of the movement. For a judoka, this might mean deciding to execute a particular throw to off-balance and throw the opponent.

- Selecting the appropriate action: Based on the movement goal, an appropriate technique is chosen, considering the situation. This includes deciding which throw, combination, or timing will be most effective to achieve the goal.

- Execution of the movement: The selected technique is performed accurately and controlled, optimizing precision, timing, and strength to achieve the intended result.

These three phases do not proceed linearly; they overlap and continuously influence each other. During the learning process, there is interplay between cognitive planning (pre-thinking strategies), sensorimotor adaptation (continuously adjusting movements based on sensory feedback), and behavioral refinement (improving motor behavior through experience). This dynamic allows a judoka to respond flexibly to variable circumstances, such as changing opponent strategies or physical fatigue.

For example: a judoka decides to perform a throw to score (movement goal), chooses the technique o-goshi based on the opponent’s position (action selection), and adjusts balance and timing during execution to successfully complete the throw (execution). If the opponent reacts unexpectedly, the judoka quickly switches to an alternative direction with a different technique or modifies the current throw, demonstrating the adaptive nature of motor learning.

This ongoing interplay of thinking, feeling, and moving is crucial for the development of motor skills.

Feedback

Feedback is an important part of motor learning. It includes all forms of information a sportsperson receives about their movement performance—such as visual signals (e.g., seeing how the opponent reacts), tactile information (the grip on the judogi and sensing what’s happening or needed), and proprioceptive input (the sense of body posture and movement). This feedback enables the brain to adjust movements and improve the motor plan.

Error processing involves recognizing and correcting deviations from the desired movement goal. This process can happen both unconsciously and automatically (implicit learning), as well as consciously (explicit learning). For instance, a judoka noticing their throw is not going well might make small adjustments in grip or balance without thinking (implicit), while simultaneously consciously reflecting on what to do differently, like choosing a different technique better suited to the situation (explicit).

Research shows that how feedback is given greatly affects the learning process. Positive, success-oriented feedback is more effective than error-focused feedback. When feedback emphasizes what goes well, it activates the brain’s reward system, boosting motivation and facilitating learning. Conversely, negative or error-focused feedback can cause uncertainty, tension, and reduced willingness to learn, even if the information is accurate.

Normative feedback, which compares performance against others, is powerful but has two sides. Positive comparisons (“you perform above average”) can enhance confidence and motivation, improving learning. Negative comparisons can discourage and hinder the learning process.

The combination of intrinsic sensations (like the feeling of grip and its effect on the movement goal) and received feedback enables the motor system to analyze errors and exhibit adaptive behavior. Adaptation occurs because the brain makes better predictions about the effects of movements and constantly fine-tunes based on new input. This leads to increasingly accurate movement patterns.

For judokas, this means learning to notice subtle changes such as feeling that their grip is weakening, or seeing the opponent move unexpectedly, and responding quickly by adjusting technique. Thus, it is not only repetition that drives motor learning, but especially how feedback is used to refine movements and better align them with continually changing match situations.

Implicit and explicit learning

Motor learning often seems automatic and unconscious but usually starts with conscious learning and attentive effort. For a beginner judoka, this means following explicit instructions, imitating movements, and actively thinking about techniques. This is called explicit learning: a conscious, cognitive form of learning where attention, memory, and strategies matter.

Continue reading HERE…